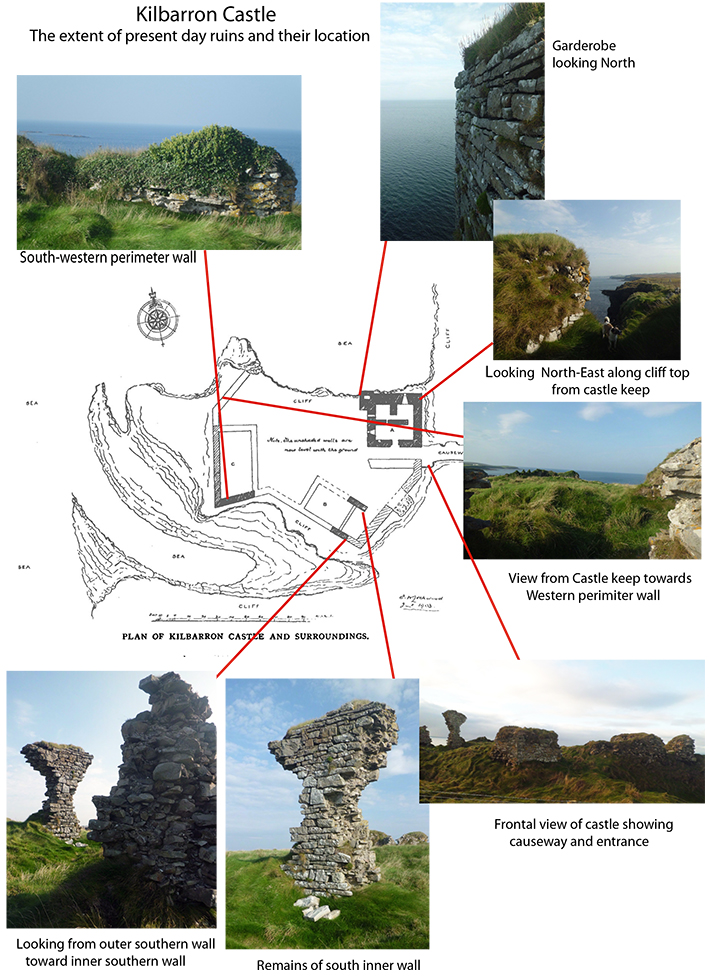

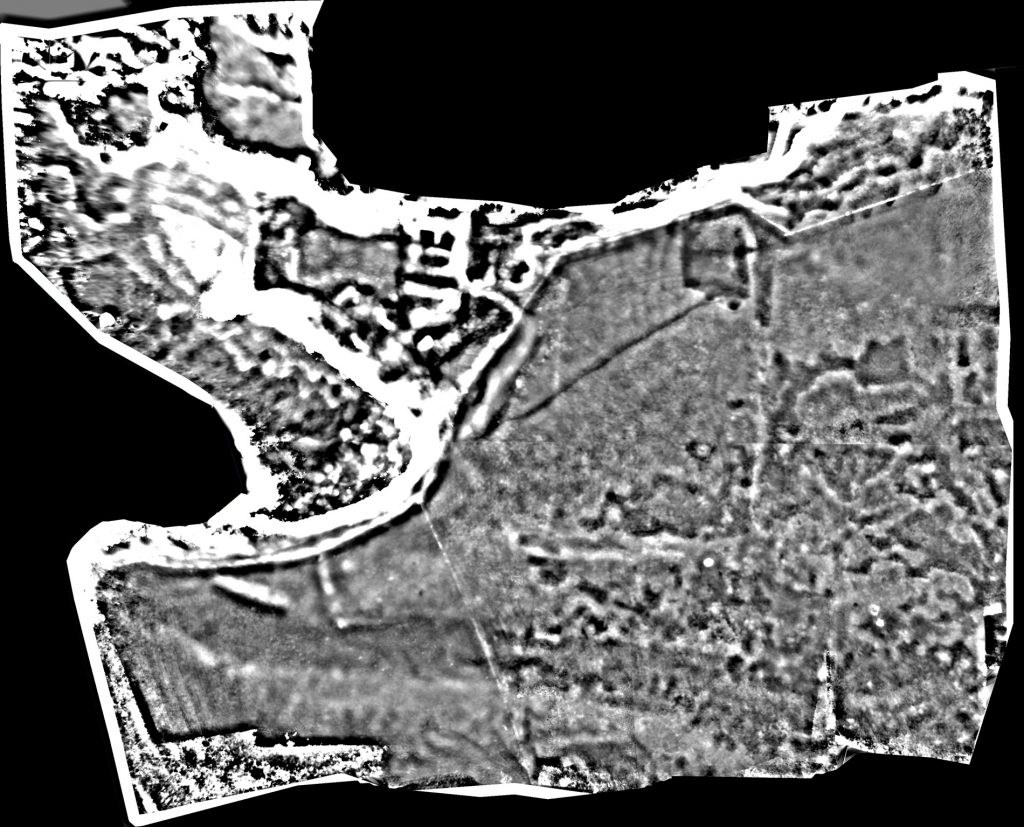

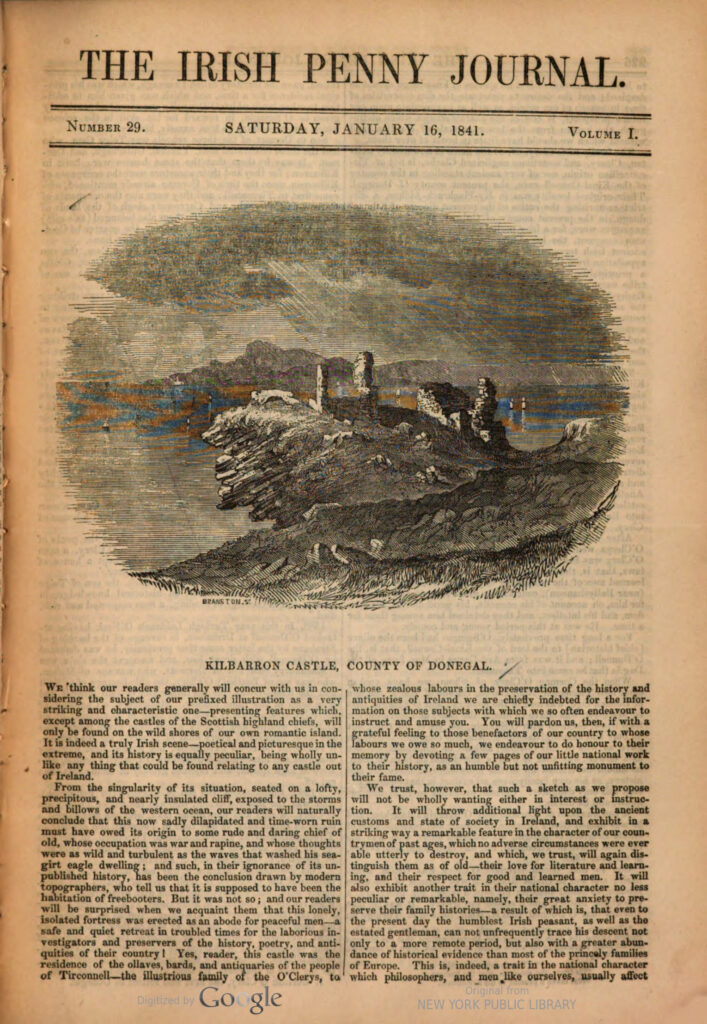

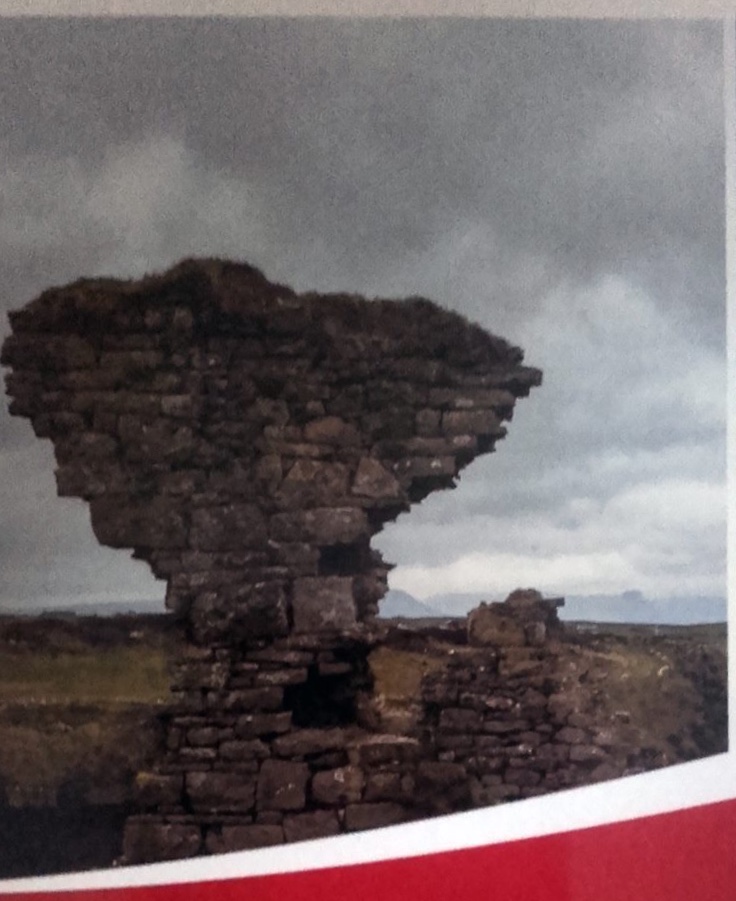

The route to the castle on the landward side leads to a narrow causeway over a deep ditch. It must have been a very defensible location but perhaps not too sheltered or comfortable whenever there was a raging Atlantic storm!

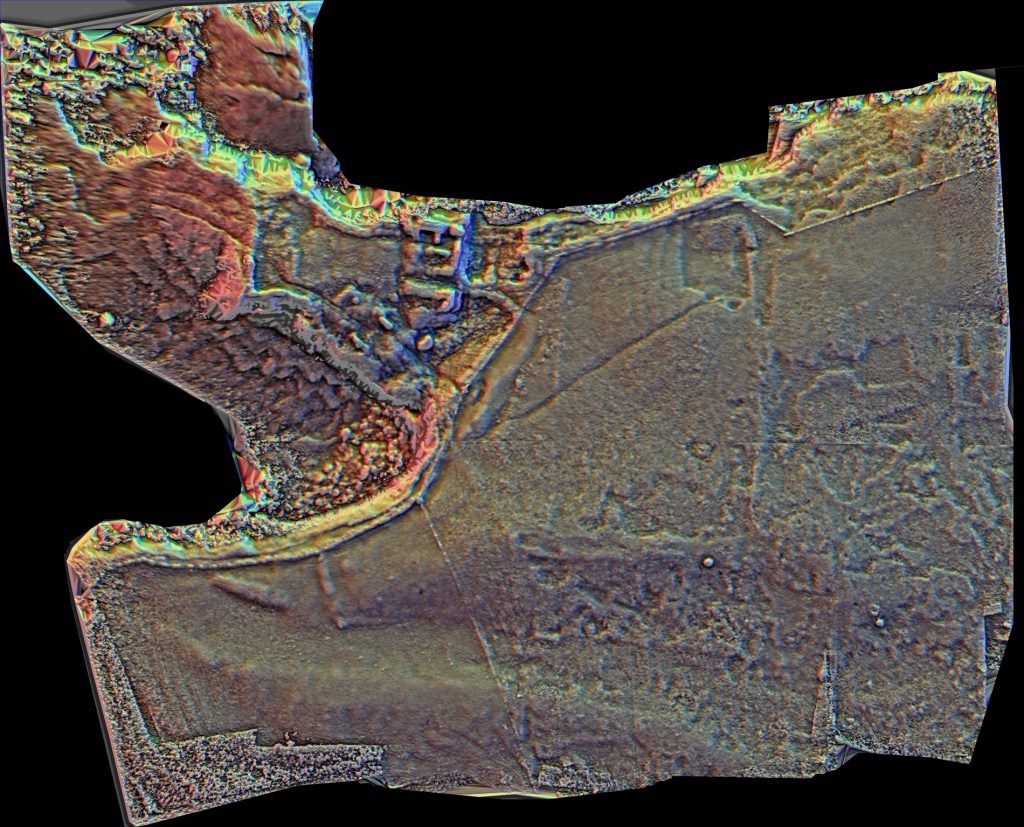

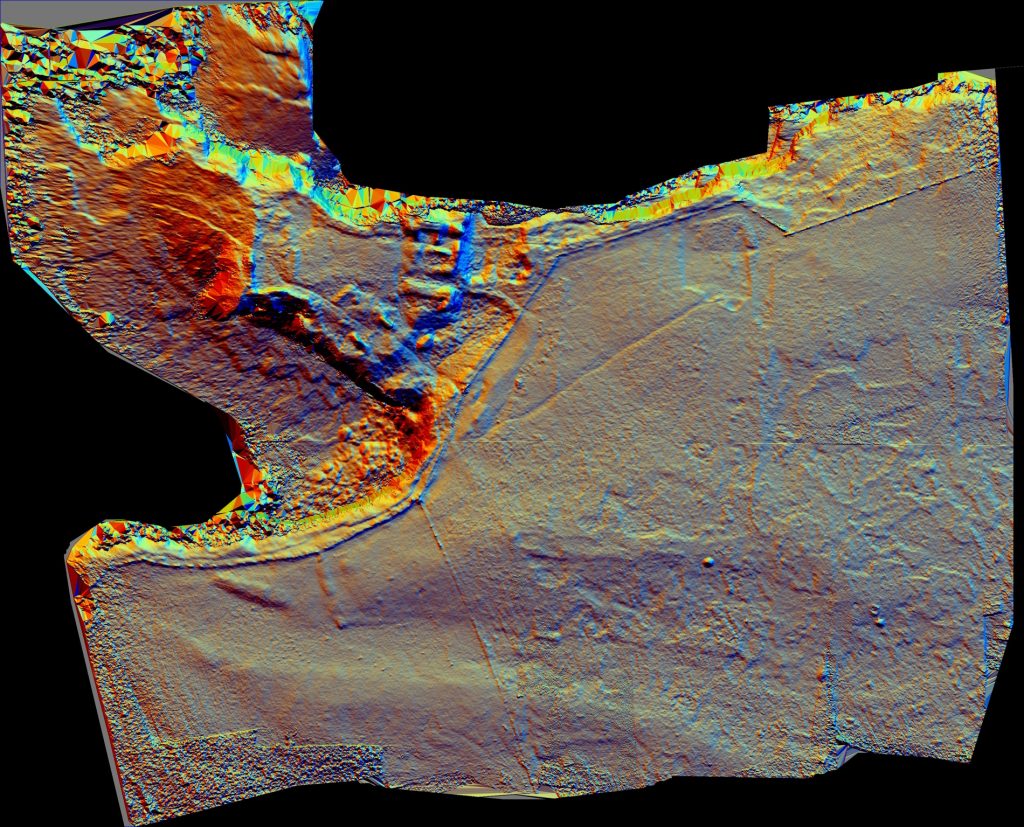

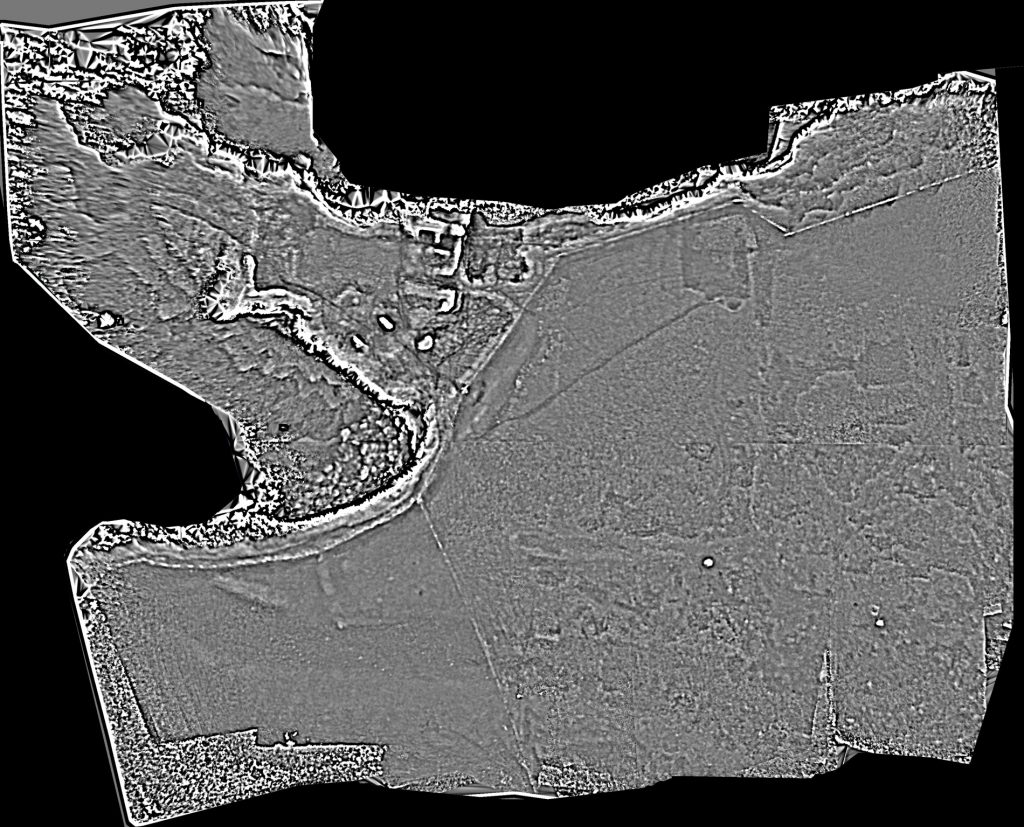

For anybody who has visited the ruins of the Kilbarron Castle the first thing you notice is that the ruins are perched on a rocky promontory jutting into Donegal Bay and surrounded by cliffs on three sides lapped by the Atlantic waves.

The site is much older than the existing stone walls would suggest as these walls date from the early 14th Century. The Kilbarron Castle Conservation Report of 2014 estimated that the place began as an Iron Age settlement.

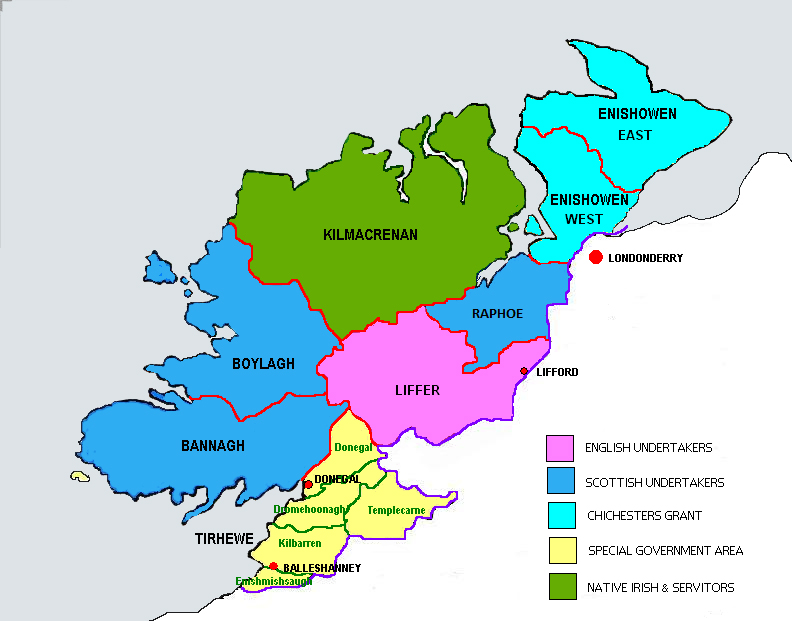

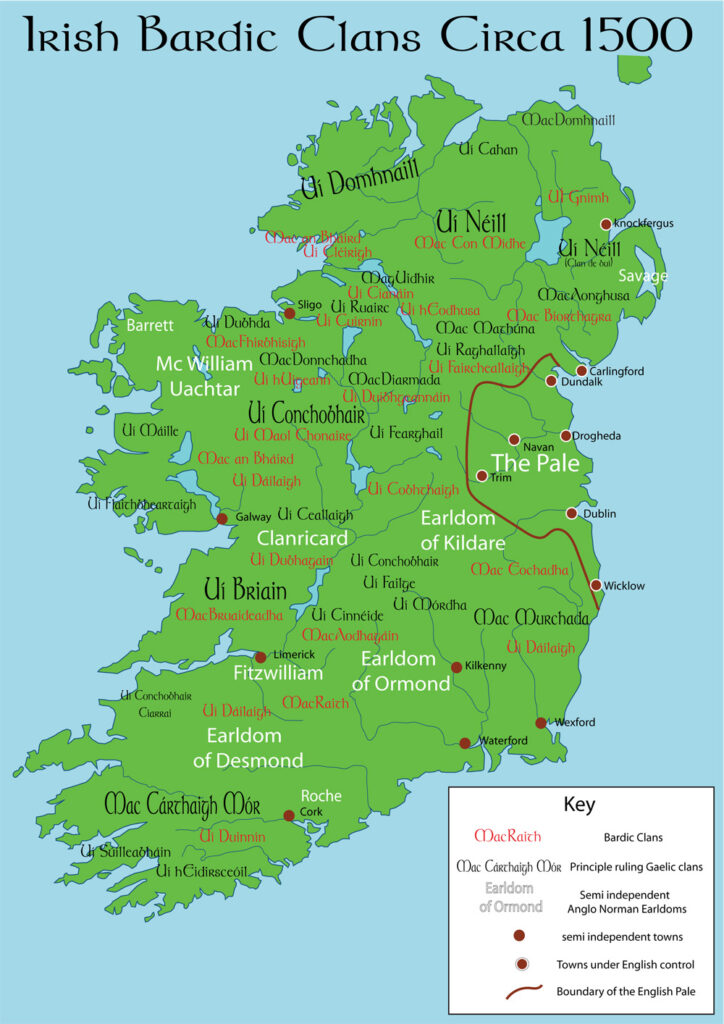

We do not yet know much about this early settlement but by the 7th Century the area between the River Erne and the Ballintra River was under the control of the Uí Maoildoraidh clan who were centred in or near Droim Thuama (Drumholm). The territory north of this to the River Eske was ruled by the Uí Canannáin clan. They both shared common ancestry and the kingship of the Cenél Connaill but were often in bitter rivalry.

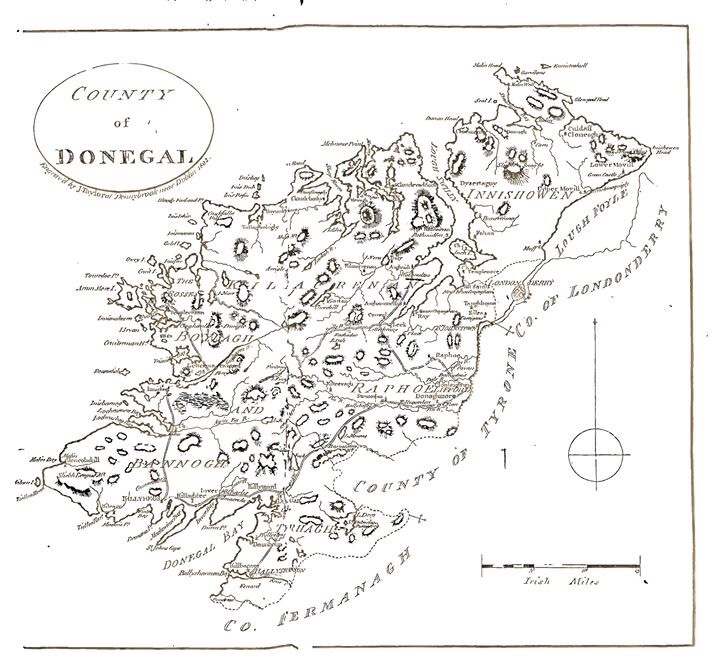

We have a map to help, see Castle Locality

Further south from Kilbarron on the Erne estuary is a similar promontory fort called Dún Cremthain (Dungravenan) there in 650 AD two factions of the Cenél Conaill fought each other for supremacy. This battle of Dún Cremthain is referred to in the “Annals of Ulster”.

In 1178 Flaghertagih Uí Maoildoraidh founded the Abbey Assaroe. He is buried in Drumhome (Drumholm) Old Graveyard and his death was to signify the end of the Kingship of the Uí Maoildoraidhs and soon after that the Kingship of the Uí Canannáins as a new power was coming into prominence from the north western part of Tír Conaill.

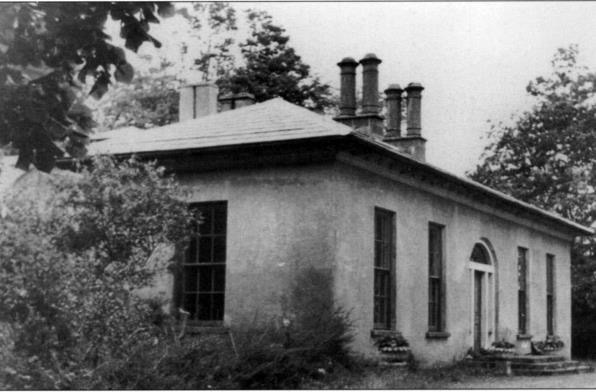

The parish gets its name from this ancient church and Flahertaigh Uí Maoildoraigh, King of the Cenél Conaill is buried here.

Drumhome Old Church Graveyard is part of the site of Drumhome monastery, which was founded by the monks of Columcille in the sixth century. The Graveyard is still used as a burial ground.

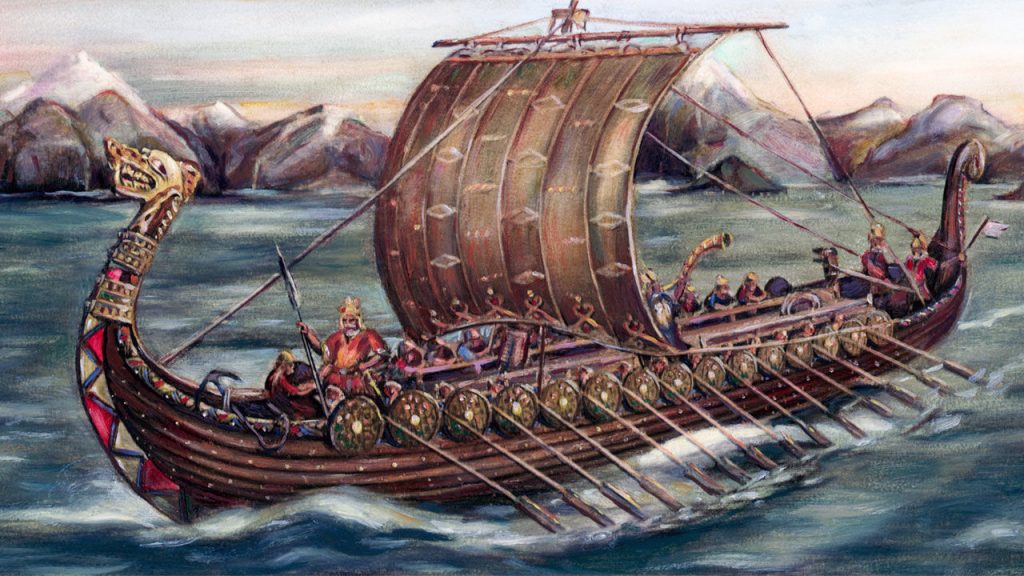

In the 10th Century the Norsemen or Vikings began raiding and plundering the coastal areas of Ireland travelling along the rivers systems as the Erne and Shannon to attack and plunder such monasteries as Devenish and Clonmacnoise, However by the 11th Century they had settled down somewhat in the coastal areas trading and founding such modern coastal cities as Dublin, Waterford, Cork, Limerick and Galway.

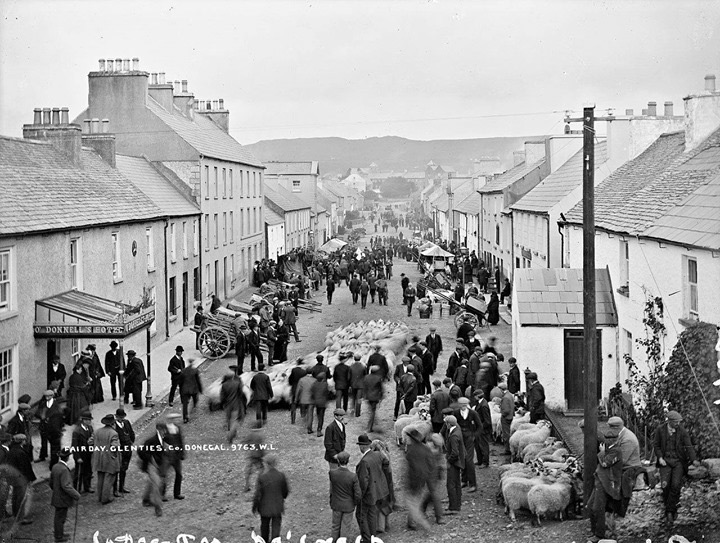

Not as well known is that they also founded trading stations at Ath Seanaidh Ballyshannon and Donegal, the latter in the Irish language, Dún nan Gall means the “fort of the foreigners” testifying to its Viking foundation. The Cinél Connaill by and large were content to allow such trading posts and would have exacted a tribute to allow them to continue their trading operations.